Clevelanders Struggle To Get Help With Utility Bills!

FEATURED PHOTO: KEVIN J. NOWAK EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CLEVELAND HOUSING NETWORK

IdeastreamPublicMedia.org, By Conor Morris and Michael Indriolo, Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative

Rashidah Abdulhaqq worries her electricity and heat will be shut off.

These are vital services during normal times, but especially during the winter, and especially when she has a portable oxygen tank she carts around to keep herself alive. Flanked by several windows wrapped in plastic to better insulate her drafty Glenville home, Abdulhaqq said she’s been trying for almost three months to get an application in for several programs to help her with her utility bills.

But despite her efforts, it’s been slow to get assistance from Cleveland nonprofit CHN Housing Partners, one of two agencies in Cuyahoga County where residents can apply for HEAP and PIPP–two utility bill assistance programs.

The Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) provides a once-per-season emergency payment for low-income people who are behind on utility bills, while the Percentage of Income Payment Plan (PIPP) provides discounted bills to the same population.

“They have this number that you call and it is constantly busy, and you can never get through the line. Plus, I can’t even schedule the appointments online,” Abdulhaqq said. The online appointment scheduler constantly says all appointments are taken, she explained.

Abdulhaqq did recently get an appointment through CHN, but only after roughly three months of seeking one. The appointment is set for late March. Meanwhile, she received disconnection notices for most of her utilities in February.

Abdulhaqq is one of a number of residents in Cuyahoga County who have sought help to pay their utility bills in winter, but have been unable to get through the bureaucracy to actually receive assistance. Extensive paperwork that must be resubmitted every year, not enough available appointments, and difficulty calling anyone directly who can help are some of the barriers.

A mother of four, Abdulhaqq isn’t currently working because she has lupus, an autoimmune disease, so she relies on her daughters who are old enough to work to help her out. She requires an oxygen tank, which makes her electric bill even higher, because the disease attacks her lungs.

Editor’s note: Rashidah Abdulhaqq, featured in this story is the daughter of Rashidah Abdulhaqq, who has done freelance reporting for NEOSOJO.

Stockyards resident Robin Turner is also far behind on her bills. Turner, a mental health specialist, has received disconnection notices for both her gas and electric. She said she’s been trying for several months to reverify her enrollment in the PIPP program through CHN and get any other help they offer. So far, she’s run into similar issues.

Turner had submitted paper copies of her applications and documents on multiple occasions over the last several months, but she was told she didn’t provide the correct paperwork. It took her almost a month to finally correct those issues and get an appointment to be put on the program, which is now set for early March.

“When you go and ask for help, the system is intentionally set up so that they take people through all these loopholes and nothing ever happens,” she said. “All I needed to do is be reverified. No one reaches out to you. No one says, ‘Hey, this is what we can do, just fax over this.’”

To CHN’s credit, when approached about these issues by a reporter, a representative did reach out to both Turner and Abdulhaqq to help them through the process.

Tony Millsaps, a Garfield Heights resident, has run into similar issues with Step Forward, a Cleveland nonprofit where people can apply for the same utility assistance programs. Millsaps quit his job as a mental health professional last year because his pay was reduced as a result of the pandemic, among other reasons. His bills are racking up, with disconnection notices for electric and gas hitting his mailbox recently.

Millsaps said he’s tried since the middle of last year to get applications in for energy bill assistance, to little avail.

“I’ve mailed (an application). I’ve gone online. I’ve faxed it. I even took it personally down there and talked to them,” he said.

Millsaps did recently get a breakthrough: He was approved for Step Forward’s emergency COVID-19-related assistance. But he was left with no word on when the help would arrive.

Taylor Wilson, a spokesperson for Step Forward, declined to comment on Millsaps’ case directly, but says winter is the “busy season” for her agency. She suggested applicants check the online scheduling system “as often as possible” for HEAP and PIPP appointments, with new appointments usually available at the top of each hour.

Why is this happening?

CHN Spokesperson Laura Boustani said the biggest reason applications can be delayed is because of missing paperwork. Programs for utility assistance often require extensive documentation from applicants, including birth certificates for all household members and pay stubs from everyone in the house who’s working.

Boustani explained that between Step Forward and CHN, which share an online application system for HEAP and PIPP, there are about 90 appointments available each day for those programs in Cuyahoga County, but they can be taken quickly each hour. CHN has also been understaffed in recent months, and with demand high for these services, Boustani said it can be hard to keep up.

“We had gone to the state last year and said we need more resources to open up more appointments,” she said. “And we got that. What we’re finding now is that it’s still an issue because the need continues to grow.”

Michelle Graff has studied the HEAP program extensively. She’s an assistant professor at the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University. In Ohio, typically only about 20-25% of the income-eligible population participates in HEAP. Other federal assistance programs like SNAP, the program known as “food stamps,” typically boast a 65% participation rate, and for Medicare, it’s even higher, almost 100%, Graff said.

As to why that is, Graff said she’s studying that issue. She does think it might have something to do with the concept of “administrative burden.” That refers to the burden placed on people to prove they are eligible for programs. CHN and Step Forward ask people to come up with pay stubs and birth certificates, for example.

“(Those) applications have you jump through these hoops and overcome these hurdles to access them,” she said.

Meanwhile, the PIPP program requires people to reverify their income each year and report if they have a change in income in order to keep participating in the program. If they fail to do so, participants can be dropped from the program. They must pay any missed PIPP bills, plus any missed non-PIPP utility bills, before they can be put back on the program.

According to public records provided by the Ohio Department of Development, there were about 55,000 enrollments and reverifications for the PIPP program in Cuyahoga County alone in 2018, but also 8,616 people who were dropped from the program because they failed to reverify.

Graff and other researchers with the Energy Justice Lab at Indiana University conducted a national survey of low-income people (below 200% of the poverty line) about their energy bills, and found one in four were unable to pay one or more energy bills between 2020 and 2021. That translates to potentially 23.5 million Americans. That statistic was even higher for Black (38%) and Hispanic respondents (34%).

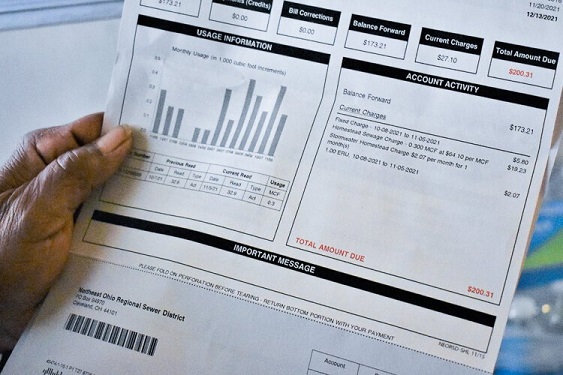

Turner, the Stockyards resident, said it’s hard for her to take care of her family on one salary, especially when her energy bills are typically through the roof. She said her utility bills totaled almost $600 in January. That could partly be a result of faulty wiring in her home, in addition to increased costs to heat the home during the winter.

Turner also faced a shut-off notice from the Illuminating Company last summer, when she owed upward of $1,000 on her electric bill, and a worker came by her home to shut her service off.

“The guy said I’m here to disconnect your service,’” she said. “Right at that moment I had to pay him (the company) $500 to keep my electricity on.”

That’s company procedure, said Lauren Siburkus, a spokesperson for the Illuminating Company. Technicians always give customers a last-minute chance to pay their past-due balance before shutting off their power. But it’s a last resort after making phone calls and sending letters in the mail with instructions about the company’s payment plan options. Even Siburkis acknowledged that getting assistance usually isn’t easy.

“There’s a lot of work and a lot of wait times that go into securing those assistances and those funds,” she said. “It is a challenge and unfortunately, really the only answer to that is that you just have to, unfortunately, endure those long waits.”

For those with health issues, enduring long waits may not be an option.

The guy said I’m here to disconnect your service. Right at that moment I had to pay him (the company) $500 to keep my electricity on. – Robin Turner

People who rely on medical devices, like Abdulhaqq, can get medical certificates filled out by their doctors to push back utility shutoffs, but the forms are only valid for one month each. Abdulhaqq said she’s had to rely on multiple medical waivers over the last year to keep her power on (you can use a maximum of three per year).

“It probably doesn’t do very much because they get a month to come up with the money,” said Constance Magoulias, a MetroHealth doctor who frequently fills out medical certificates for patients. “If they don’t have the money, then I don’t know how well it helps you.”

Losing electricity makes storing fresh fruits and vegetables nearly impossible, over time leading to nutritional deficiencies and poor health, Magoulias said. That’s of particular concern for people with diabetes because they need refrigeration to store insulin and specific foods to survive. Additionally, people on blood pressure medication, which can cause dizziness, are particularly vulnerable to fainting on hot summer days, and losing power makes staying cool much harder. Those with asthma, too, may need a special electronic device called a nebulizer to take their medicine.

Those conditions, diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure, all disproportionately impact Black residents on the city’s East Side, according to The Center for Community Solutions.

Abdulhaqq, the Glenville resident, suggested one possible solution: Create a different building or department within local utility assistance providers to specifically serve people with serious health conditions.

“That would make it a lot easier… and faster,” she said.

Meanwhile, U.S. President Joe Biden signed an executive order in December meant to improve the experience of people applying for government assistance programs. That order specifically mentions SNAP, Medicare and Social Security.

There is no reference to the energy assistance programs HEAP and PIPP, however.

This story is a part of the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative’s Making Ends Meet project. NEO SoJo is composed of 18-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including WKSU and Ideastream Public Media. Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America, and Michael Indriolo is a reporting fellow for The Land. Email Conor at [email protected], or Michael at [email protected].