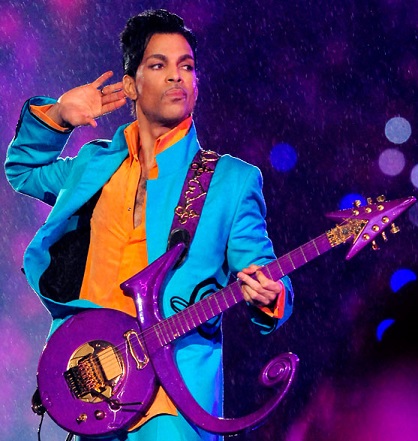

‘Was I What You Wanted Me To Be?’ How Prince Challenged The Racial Conventions Of Genre!

TheGrio.com, By Matthew Allen, Posted August 10th 2023

Opinion: Part three of theGrio’s four-part series on Prince analyzes how he reappropriated rock and other genres considered to be white by fusing them into his funky core, thus elevating him to legend status.

Prince didn’t believe in categories. In his 1981 single, “Controversy,” he asked, “Am I Black or white? Am I straight or gay?” Ambiguity became his calling card in both his image and his artistry. He strived to be undefinable in all ways.

Public Enemy frontman Chuck D said during a panel discussion at Paisley Park’s Celebration 2023 that his first impression of Prince was that he was “a little Duke Ellington.” Sir Duke notoriously coined the phrase that there are only two kinds of music; good and bad. Prince embodied Ellington’s virtuoso composing acumen and his sentiment that music goes beyond categorization.

One of Prince’s most significant benefits as a songwriter and musician came as a result of his birthplace. Minneapolis was a city bereft of musical identity. Because of that, Prince was exposed to various sound sources and artists in his formative years. L. Londell McMillan, Prince’s former lawyer, and organizer of his estate, explained how Prince’s birth city molded his sound.

“What was poured into him, being in Minneapolis, was a very cross-section of music from all walks of life,” McMillan told theGrio. He went on to say that Carlos Santana was as pivotal an influence on Prince as James Brown, Little Richard, Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix were.

“He was also in an area where there wasn’t nationally programmed radio by a few major media companies who played the same thing,” McMillan continued. “But each area had its own local radio formats and radio show programmers that played music they felt their audience wanted to hear in Minneapolis. You had to hear a lot of music that stereotypically is called white music, but it was more a pop, rock-ish kind of thing. But he was able to get it all, and he was able to take it in.”

Prince’s first two albums, 1978’s “For You” and 1979’s self-titled LP, were chiefly executed like the funk and R&B of the moment. But the song “Bambi” on the latter signaled his incorporation of heavy rock into his work.

By 1980’s “Dirty Mind,” songs like “When You Were Mine” and “Gotta Broken Heart Again” saw Prince modernizing an almost bygone sense of rockabilly and garage rock that was rare from Black acts and foreign to white people’s ears in that era. Once he reached “Purple Rain” in 1984, the fusion of genres claimed by whites like rock (“Let’s Go Crazy”), folk (“Take Me With You”), and even tinges of country-western (the title track), Prince reclaimed for himself and Black people in perpetuity.

Three of Prince’s five No. 1 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 charts had notable injections of rock elements — 1984’s “Let’s Go Crazy” and “When Doves Cry” and 1991’s “Cream.” On top of such success, his lead guitar ability steadily grew into the realm of the peerless, evident in songs like “Scandalous,” “Shhh…” and his infamous solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” in the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s tribute to George Harrison.

After standing on the shoulders of Hendrix, Funkadelic’s Eddie Hazel and Bootsy Collins, and blues stalwarts B.B. King and Albert King, Prince’s acceptance in pop music on a global scale as a Black artist helped smooth the road for Black artists like Lenny Kravitz and Living Colour to thrive in genres and lanes that otherwise would’ve been blocked to them.

Aside from rock, Prince found time to inject classical music into his arsenal. When it came time to craft “Parade,” the soundtrack to his 1986 film, “Under the Cherry Moon,” fans and critics alike were impressed with his mixing of classical elements into his now signature sound.

The arrangements and sequencing of “Parade” operate more as musical movements, à la Vivaldi or Beethoven, than a conventional album tracklist. Side A particularly finds Prince utilizing new instruments with his growing idiosyncratic compositional calling cards. Songs like “New Position,” “Christopher Tracy’s Parade,” “Life Can Be So Nice,” and “Sometimes It Snows in April” were illustrations of a newfound symphonic sensibility not usually associated with Black artists outside of Quincy Jones or Isaac Hayes.

Prince took his aptitude for classical to an extreme on 1988’s “Lovesexy.” He released the album’s CD version, placing all nine songs on one single track. With CD technology still in its infancy, it forced the listener to take in “Lovesexy” not as an album you can skip from track to track, but as a singular musical suite. Prince challenged his fans with this move in the same spirit Stravinsky challenged his with “The Rite of Spring.” And like “Rite of Spring,” “Lovesexy” wouldn’t get its due until years later.

Even beyond rock, Prince excelled in so-called jazz with his instrumental Madhouse albums, his involvement in saxophonist Eric Leeds’ “Times Squared” album in 1991, and his own “N·E·W·S” album in 2003. He even dabbled in hip-hop production and rap, despite having an on-again, off-again aversion to the music.

Nevertheless, Prince strengthened his popularity by fusing genres connected closely to white people into the roots of his artistry — Midwestern funk. By growing up in a city with no musical identity, he sparked a movement that led to what the world now knows as the Minneapolis Sound.

Prince’s legacy will continue to grow because he refused to be boxed into a category, the ultimate musical taboo and controversy. For the man who wrote, “I wish there was no black and white, I wish there were no rules,” he didn’t wait for someone else to make his wish come true.

Matthew Allen is an entertainment writer of music and culture for theGrio. He is an award-winning music journalist, TV producer and director based in Brooklyn, NY. He’s interviewed the likes of Quincy Jones, Jill Scott, Smokey Robinson and more for publications such as Ebony, Jet, The Root, Village Voice, Wax Poetics, Revive Music, Okayplayer, and Soulhead. His video work can be seen on PBS/All Arts, Brooklyn Free Speech TV and BRIC TV.