MXO Black History Moment: The Racism That Drove Lynchings 100 Years Ago Persists Today, In More Subtle Ways!

FEATURED PHOTO: ELIAS CLAYTON, ISAAC MCGHIE AND ELMER JACKSON MEMORIAL IN DULUTH MINNESOTA

Yahoo.com, By Michael C. Seeger-THE DESERT SUN, Posted February 22nd 2022

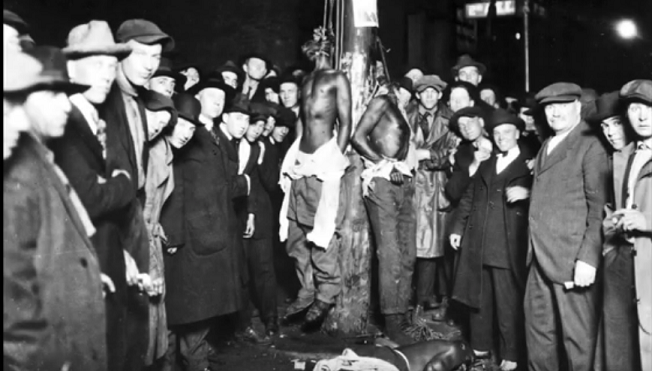

Over 100 years ago in Duluth, Minnesota, three Black circus workers — Elias Clayton, Isaac McGhie, and Elmer Jackson — were (falsely) accused of raping a young white girl and lynched by a mob of about 7,500 people.

Bob Dylan wrote a song in 1965 entitled “Desolation Row,” whose opening lines appear to reference the racially fueled crime in Duluth — Dylan’s birthplace — 45 years earlier.

Meeting little or no resistance from the police, who were ordered by the city’s public safety officer (the “blind commissioner” in Dylan’s song) to holster their weapons, a lynch mob descended on the Duluth jailhouse, extracted the three men, hung them from a lamppost, and proudly posed for photographs with the victims’ corpses afterwards.

And that was in the North.

An estimated 4,084 African Americans were lynched in the South between 1875 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Institute, averaging more than one hanging a week during that 75-year period. The crimes largely targeted Black people, but not exclusively: 149 people of Mexican descent were lynched in a forgotten piece of California history between 1848 and 1859.

Lynching — the nebulous term evokes frightening images of maliciously unjust, racially fueled mob torture and public violence.

And for good reason.

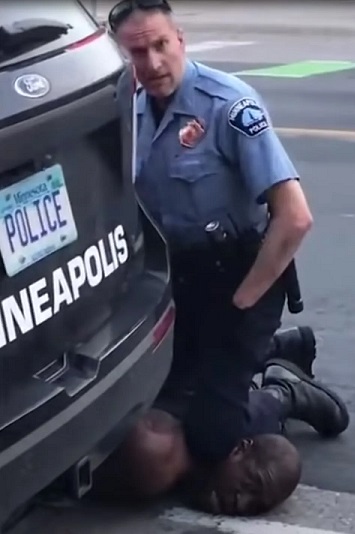

Systemic racism and the “lynching effect” of social injustice continue to this day. The atrocious killing of George Floyd in 2020 — 100 years after the Duluth lynching — is only one recent example of dehumanizing abuse of power.

Though they’re mostly manifested in imperceptible, structural ways, it’s quite evident that ethno-racial injustice and discrimination have very palpable consequences for their victims.

I’ve worked in the east valley for more than 20 years, and it’s become increasingly clear that those children born into households deprived of economic opportunities and human capital are less likely to escape their impoverished circumstances.

For this very reason, these excluded groups require special consideration, support and “a voice” to express their needs and concerns. If we neglect to address the causes of structural discrimination, not only will we be perpetuating injustice, but a huge opportunity for all will be lost.

Nearly 60 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prejudice against Black people and other people of color is rife among Americans, and vicious outbreaks of its presence continue as seen on TV.

And the riot squad they’re restless, they need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight, from Desolation Row.

The Coachella Valley Historic Museum sits on the former ranch land of Indio pioneer John Nobles (who lived from about the 1880s to the 1940s), the first Black person to own large tracts of land in the Coachella Valley.

Conditions were bleak back in those days — the effectual segregation of African Americans, Latinos and Native people prevented access to clubs, hotel lodging and other basic rights.

Nobles, in his way, spoke out against racial injustice in assisting many fellow Black Americans to settle and establish roots in the valley at a time when it was rare for Black and Latino people to own land in the area.

It is Nobles’ spirit and example we must adopt in speaking out against racial injustice everywhere — and thereby contributing to making a more peaceful world.

Our silence would be the real violence.

Michael C. Seeger, a poet, writer and educator, lives in Cathedral City. Email him at [email protected].