Opinion: The Surprising Second Life Of The Supreme Court’s Abortion Decision!

Yahoo.com, By CNN-Opinion, Posted July 20th 2023

Editor’s Note: Mary Ziegler is the Martin Luther King Professor of Law at UC Davis. She is the author of “Dollars for Life: The Antiabortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment” and “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

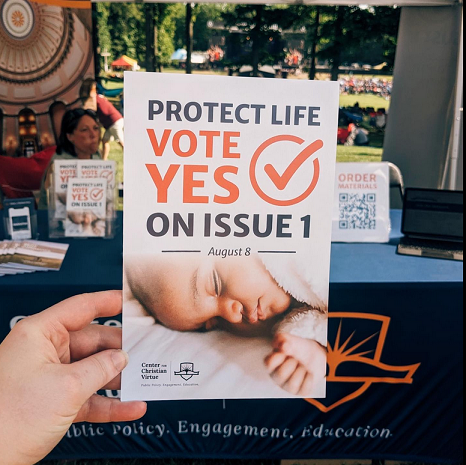

In Ohio, Republicans seeking to defeat a ballot initiative creating a state constitutional right to abortion have seized on another culture war issue: gender-affirming care. An ongoing ad campaign, initiated by anti-abortion group Protect Women Ohio, claims that the Ohio measure would allow minors to get gender-affirming care without parental consent. Those ads have been debunked — the ballot initiative says nothing about gender identity and has no impact on gender-affirming care. But there may be a surprising connection between abortion and gender-affirming care after all — one developed by conservatives, a reinvention of the Supreme Court’s decision destroying federal abortion rights.

This year, 19 states have enacted restrictions or bans on gender-affirming care, but many of these laws have quickly faced constitutional challenges in court. Federal judges in Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky and Indiana issued rulings blocking these state measures from taking effect. But now, an appellate court has recently upheld a state ban: A three-judge panel of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals allowed Tennessee’s ban to go into effect while litigation continues in the lower courts (a formal decision on the state’s appeal of the preliminary injunction is expected by the end of September). Central to the panel’s decision was the Supreme Court’s decision overruling Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Center.

It may not seem surprising for a conservative court to rely on Dobbs in a case involving trans youth. There is certainly a political connection: Any states that ban gender-affirming care also have taken steps to criminalize abortion.

But in the Sixth Circuit case, L.W. v. Skrmetti, three transgender minors, their parents and a physician argued that there was no constitutional connection between Dobbs and gender-affirming care. They contended that the court has long recognized constitutional rights for parents to direct the upbringing of their children — including crucial medical decisions about their care. If the Supreme Court in Dobbs recognized only rights honored since the nation’s founding, surely parental rights qualified.

The parents and minors also asserted that Tennessee’s law amounted to unconstitutional sex discrimination. In the context of federal employment discrimination, in Bostock v. Clayton County, the Supreme Court held in 2020 that discrimination on the basis of gender identity (or sexual orientation) always counted as sex discrimination. The plaintiffs in L.W. suggested that the same was true when it came to gender-affirming care. As US District Judge Eli Richardson, a Trump nominee, explained in ruling for the minors and their parents, a minor’s genetic sex determined whether they could access certain treatments, and that made Tennessee’s law a sex classification.

The Sixth Circuit panel, in their ruling, first used Dobbs to reframe what the minors and their parents were saying: The court positioned their claim not as a vindication of parental rights, but as a demand to access “new medical treatments.” This right, the court reasoned, was not deeply rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.

What was more surprising was that the court held out Dobbs as a new paradigm for sex discrimination. This is striking because Dobbs itself said so little about sex equality. For years, the leading constitutional argument against abortion bans involved sex discrimination — claims that abortion bans rested on sex stereotypes, for example. Even though neither party had even fully briefed these claims, the Dobbs court reached out to reject them anyway in a terse paragraph, suggesting that past precedent established that discrimination on the basis of pregnancy or a related condition did not qualify as sex discrimination.

The Dobbs court barely said enough to offer a coherent response to arguments that abortion bans involved sex discrimination. And yet Tennessee — and the Sixth Circuit panel — saw it as a new model for sex discrimination law.

What counted under Dobbs, this recent ruling suggested, was that bans on both abortion and gender-affirming care involved “real” biological, reproductive differences, not sex stereotypes. Banning a medical procedure, then, had nothing to do with sex discrimination unless the state used that “real” difference as a pretext for bias.

Set aside, for the moment, that someone could see the state’s actions as pretextual, given that Tennessee has shown hostility to LGBTQ Americans across other contexts, prohibiting medical coverage for gender-affirming care for adults working for the state and banning drag shows — a law that a court recently held to be unconstitutional.

The court treated Dobbs as the start of an overhaul of sex equality law. At the center of this was Dobbs’ reliance on a 1974 decision, Geduldig v. Aiello, which held that pregnancy discrimination was not unconstitutional because sex and pregnancy were not perfectly aligned (not all women, for example, were pregnant at all times). Geduldig was reviled by pro-life as well as pro-choice Americans, who campaigned for a federal law banning pregnancy discrimination, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, in 1978. As Congress recognized in 1978, “the assumption that women will become pregnant and leave the labor market is at the core of the sex stereotyping.”

The Sixth Circuit, by contrast, took Geduldig as a helpful touchstone for modern law: Biological determinism could be the start of a new approach to constitutional sex discrimination, and the state could use reproductive capacity as a smokescreen for sex classifications. In theory, that means the state could discriminate on the basis of anything related to reproductive organs: pregnancy, miscarriage, stillbirth, infertility, gender-affirming care and, of course, abortion. These classifications, the Sixth Circuit suggested, were about biology, not sex stereotypes, and the Constitution allowed the state to discriminate on that basis.

The Sixth Circuit panel even seemed to read Dobbs as holding that states were simply freer to discriminate on the basis of sex in every case, not just those related to “biological difference.” Since the 1973 decision of Frontiero v. Richardson, which was decided after Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court has closely scrutinized sex classifications, generally upholding them only if they serve an important governmental interest and use means substantially related to it. That meant a wide variety of discriminatory laws were struck down — rules allowing widows but not widowers to receive certain benefits, for example, or denying men admission to nursing school or preventing women from entering intensive, military-style undergraduate programs.

In this recent case, the Sixth Circuit panel never invoked this demanding test, instead relying on an older, pre-Roe case that required deference to legislators classifying citizens on the basis of sex. As the Sixth Circuit panel read Dobbs, the Supreme Court made it easier to discriminate on the basis of sex in any context — and required courts to give states the benefit of the doubt when they draw lines based on sex, sexual orientation or gender identity.

This decision is the first chapter of a much longer story about the expansion of Dobbs. The Supreme Court already revolutionized the law of reproduction in the United States—and raised critical questions about the future of other privacy rights. But the latest decision in struggles over trans rights suggests that longstanding protections for sex equality might be on the chopping block, too.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com